Hippotherapy (from the Green work "hippos" which means "horse") is treatment thru the use of the horse.

Physical, mental, and emotional benefits have been seen by patients riding horses. Improvement is also seen in focus, attention span, concentration,

memory, and speech.

The horse's movement is quite similar to a human's movement. This can facilitate muscle memory of a client; and improve spinal alignment and balance.

Pictured is Sue Ryzdynski and Sokki fra Seitustodum who live in Las Vegas, Nevada.

A note from Sue: I was reluctant to talk much about this, as Icelandic Horses, have

attributes that are perfect for many riders. Because of my imbalance and

uncoordination, I did select a breed that would not spook as easily.

The Icelandics don't have as much of

the "fright or flight" instinct, that

"standard" horses have. They "startle", but just go a few steps faster,

not enough to unseat you.

They're loyal, protective, surefooted, smooth, great temperaments, easy

to handle and the list goes on and on...

Sound to good to be true? Not with this breed.

He's flexible, easy to ride and a little extra training that was

necessary, he took in stride easily.

If you want more information, contact me:

rynzdynski@juno.com

Home Page of Sue and Sokki

The Best Medicine

When a painful back injury sidelined her rider, an Icelandic mare took on the role of physical therapist par excellence.

By Theresa I. Jordan

Stina, my Icelandic mare, has always had serious doubts about my surefootedness-and with good reason. You see, when I came to own her, she had recently arrived from her native Iceland and was unfamiliar with many of the natural attributes of the northeastern United States, particularly dense forests. Since Stina would be living in a barn located within a large, tree-laden park system, I decided to introduce her to her new surroundings very gradually by "trail walking" her, leading her by hand through increasingly wooded areas.

On one of our walks, I was watching Stina's footsteps with such fascination that I ignored my own. 1 stumbled into the remains of a rotten tree trunk and fell spread-eagle in the decaying wood and mud. It took a few seconds for me to regain my senses, and as I began to collect myself, I realized that I was still holding Stina's lead shank. She seemed unperturbed by the situation and was standing stockstill next to me, staring down as if to say, "Please get to your feet, you pathetic two-legged creature."

From that day forward, however, Stina always has been more comfortable with me astride than at her side. Whenever I walk her on a lead line, she reacts instantly to my slightest stumble, usually by bracing herself with four legs maximally spread, so as to catch a falling body.

During our first two years together, Stina and I became quite proficient at galloping along the wooded paths, jumping logs and dodging deer. Then tragedy struck. Believing myself to be a strong and well-muscled woman from all of my outdoor activities, I singlehandedly set about the task of boxing up my accumulated books. After accomplishing the mammoth job--my library filled 40 boxes -- I collapsed in the most excruciating pain I had ever experienced, the result of a herniated disc in my spine.

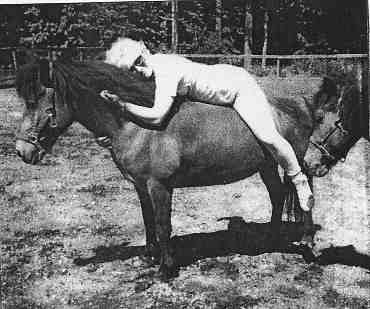

While recovering from a herniated disc in her spine, the author discovered the nurturing side of her otherwise fiery Icelandic mare, Stina.

My friends remind me now that I asked only two questions during the week I was hospitalized: First, when would I be able to ride again; and second, when would I get my next dose of Demerol. The experts who examined my back had varying answers to the first, more pressing question. Their responses ranged from "quite a while" to "as soon as you can tolerate the pain of movement."

Two days after being released from the hospital, I begged a friend to drive me to the barn. This was a major undertaking because I was not able to walk properly. As a matter of fact, I could not support the weight of my body in an upright posture. Nonetheless, I made it to the barn. As my friend let Stina out of her paddock to see me, I swung open the truck door and tried to stand up by hanging onto the top of it. Immediately, Stina, who had been moving rapidly toward me, slowed her gait and approached gingerly. I wondered if she was remembering that incident in the woods two years before or whether she had noticed my current lamehess. When she reached me, I impulsively let go of the door and wrapped my arms around her strong neck, lacing my fingers through her mane for support. This was a rather straightforward maneuver, since I'm five-foot-seven and Stina, typical for an Icelandic horse, stands at only 13 hands.

Stina is a very fiery show mare, and I knew that she could bolt from my grasp at any moment. Instead, she took one very small step, moving forward only about three inches. I followed, carefully shuffling one foot the same distance. With a watchful eye on my feet, the mare took a second tiny step, and I followed her lead. It seemed no effort for her to support my weight in this manner, so Stina became my dependable "walker"; she never moved too quickly or forgot to be mindful of my progress.

Not long afterward, I persuaded my friends to help me mount and ride my mare. After all, the last back specialist had said that the only limiting factor in my particular injury was tim level of agony I could tolerate. As I was hoisted onto Stina's back, less then two weeks post-injury, I felt tears of joy spilling all over my face. Then I asked the mare to walk, and though she moved with incredibly careful steps, my tears of joy exploded into tears of searing pain. My back could not tolerate the forward and backward sway of a horse's walk. With great help, I dismounted and draped my upper body over a nearby fence. After about 20 minutes, I had composed myself and was ready to try again. The second time was easier--I knew what to expect and could keep my back more relaxed in spite of the pain.

All during that summer, Stina was my most important physical therapist. While I went to "real" physical therapy three times a week, my human therapists felt that both my motivation and my fine muscle coordination were greatly enhanced by my progressive return to riding. There were some terrible days when riding Stina down a slight decline hurt so much that I sobbed aloud in the woods. And there were some really good days when 1 thought I was ready for more than a walk. But Stina knew better. When I asked for a trot or for the special Icelandic tolt, my headstrong mare, who never before passed up an opportunity to gallop, simply refused. So we progressed at a pace she determined, and she never shied or stumbled or did a single silly thing throughout my convalescence.

Toward the end of the summer, I was recovering more rapidly, and we were finally riding with the wind in our hair and joy in our hears. After one evening outing, I turned Stina out to cool her before feeding her. She happily ran down the rolling hill that is part of the largest paddock at our barn until she was out of sight. I already had turned to stow her tack when I realized that I had forgotten to put on her fly mask. After such a lovely ride, I couldn't bear to think of her being bothered by bugs. I fetched Stina's fly mask from my locker and headed out to find her.

Everything was fine until I began to descend the paddock's rolling hill in the twilight. The ground was uneven, and I failed to notice a ridge in front of me. Unceremoniously, I stepped into it, stumbled and fell. The worst part was that I landed in a twisted heap on the ground with my hips and legs front down and my upper body front up. Because of my injury, I was completely immobilized. Suddenly, I realized that no one knew where I was. I began to panic.

Then I heard hoofbeats, and saw Stina's familiar outline as she galloped up the hill. "Great," I thought, "now I'll be trampled as well." What a terrible lack of faith that thought betrayed. Stina slowed as she approached me, then circled me a few times, tilting her head and rotating her ears. Still uncertain that she would not step on me, I fought the urge to shoo her away. After a few minutes, she positioned herself in back of me and gently nudged her nose under my right shoulder. I remained quiet, and Stina nudged my shoulder again, this time a little harder. I rolled forward a bit, but not enough to straighten myself out. Finally, Stina pushed her whole face under my right shoulder and rolled me over. Now I was untwisted. The mare stayed very close to me with her head down. I laced my fingers through her mane and hoisted myself up to a standing position.

Now I could walk back to the barn with a tolerable amount of pain. I took two steps away from Stina, but then stopped myself. I still had the fly mask in my hand. I put it on her face and kissed her gratefully. She watched me begin walking back to the barn, then she turned. I could hear her running happily back down the hill.

Horsemanship from a Wheelchair, Michael Richardson